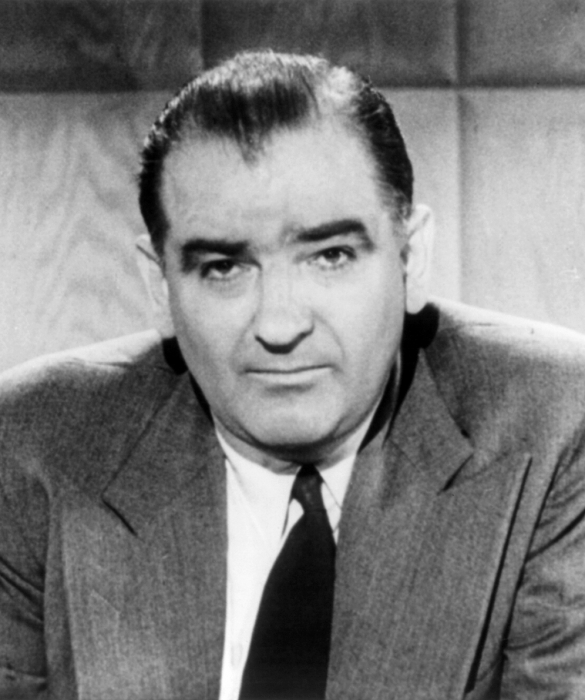

McCarthyism was a term coined to describe activities associated with Republican senator Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin. He served in the Senate from 1947 to 1957.

McCarthyism described the practice of publicly accusing government employees of disloyalty

In the American political lexicon, the term has its origin in a March 1950, Washington Post editorial cartoon by Herbert Block, who depicted the four leading Republicans trying to push an elephant to stand on a teetering stack of 10 tar buckets. The topmost Republican in the cartoon was labeled “McCarthyism.”

The term McCarthyism soon evolved to describe the practice of publicly accusing government employees of political disloyalty or subversive activities and using unsavory investigatory methods to prosecute them. The practice held sway between 1950 and 1954, a period of intense suspicion during which the U.S. government was actively engaged in countering Communism — in particular, the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).

As evidenced by congressional passage of the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, which made up Title 1 of the Internal Security Act of 1950 (also called the McCarran Act), a majority of Congress also shared the belief that CPUSA constituted an active conspiracy that was secretive and loyal to a foreign power and dedicated to the clandestine infiltration of U.S. cultural and political institutions.

The Supreme Court’s 6-2 decision in Dennis v. United States (1951) upholding the constitutionality of the convictions of CPUSA leaders Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, and ten others for advocating the violent overthrow of the U.S. government in many ways also lent constitutional support to this belief.

Ronald Reagan, actor and president of the Screen Actors Guild, listens to testimony at a public hearing of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, in 1947. Reagan, who was known for his strong anti-Communist stand, became President of the United States. The HUAC was one result of McCarthyism, the practice of publicly accusing government employees of political disloyalty or subversive activities and using unsavory investigatory methods to prosecute them. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Sen. Joseph McCarthy spearheaded investigations with little evidence

Although most scholars consider McCarthyism to be an outgrowth of the Palmer raids and the red scare of the 1920s and the Smith Act of 1940, which made it illegal to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the U.S. government, it was for the most part synonymous with Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

As chair of the Senate Committee on Government Operations and the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, McCarthy spearheaded investigations of Communist Party members and sympathizers employed either in the U.S. government or by government contractors. Anti-McCarthyites would later refer to these congressional investigations as “witch hunts.”

During his 10 years in the Senate, McCarthy and his staff gained notoriety for making outlandish accusations that, though initially directed to government employees, would later include Americans from all walks of life. Because he systematically engaged in the practice of public accusations of political disloyalty or subversion with little regard for evidence and the use of unfair investigatory methods, Senator McCarthy would later himself be accused of victimizing those who appeared before his committee and suppressing basic civil rights and liberties.

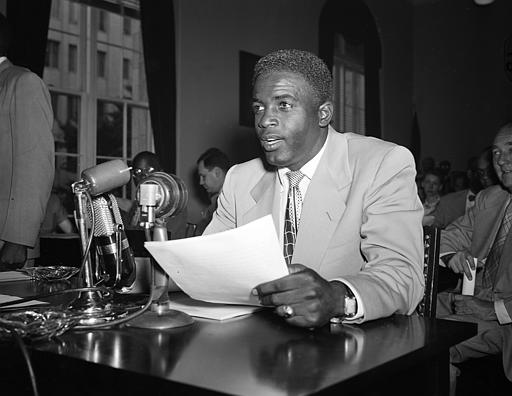

The men and women accused in both the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings had little chance to exonerate themselves once their identities were revealed to the public. Simply being accused of Communist sympathies was sufficient to damage or end many careers, because those accused could not otherwise argue their innocence. The widespread persecution of Communists and Communist sympathizers began to abate only after Senator McCarthy’s testimony in the so-called Army-McCarthy Hearings in 1954 produced an unfavorable backlash.

The men and women accused in both the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings had little chance to exonerate themselves once their identities were revealed to the public. Simply being accused of Communist sympathies was sufficient to damage or end many careers, because those accused could not otherwise argue their innocence. In this photo, Brooklyn Dodgers’ star Jackie Robinson speaks before the House Un-American Activities committee in 1949. Robinson was called to testify about the loyalty of blacks to the United States. (AP Photo/William J. Smith, used with permission from the United States)

Court put an end to McCarthyism

In 1957, the Supreme Court decision in Yates v. United States put an end to the Smith Act prosecutions by requiring that the government prove that a defendant actually took concrete steps toward the forcible overthrow of the government; merely advocating it in theory would not suffice. Because McCarthyism rested largely on smearing people’s reputations and careers rather than presenting factual evidence that supported the allegations, the Yates decision effectively put an end to such a practice.

McCarthy ruined lives of innocent people

The criticisms of McCarthyism, and of Senator McCarthy in particular, are threefold.

- First, he ruined the reputations and lives of many people by accusing them without credible evidence.

- Second, he used accusations of Communist sympathies to counterattack anyone who criticized his methods.

- And, third, he argued against freedom of speech because much of his rhetoric assumed that any discussion of the ideas underlying communism was dangerous and un-American.

The victims of McCarthyism — that is, those who were called by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and the House Un-American Activities Committee — were either denied employment in the private sector or failed government security checks. In the film industry alone, over three hundred actors, writers, and directors were denied work in the industry through the informal Hollywood blacklist, which prompted some to go into exile overseas.

From the viewpoint of McCarthy supporters, at the time it was essential to identify foreign agents and suppress “radical organizations.” McCarthy and his followers believed subversive elements posed a danger to the national security of the country and so justified such extreme measures, even if they included the denial of civil liberties.

From the viewpoint of McCarthy supporters, at the time it was essential to identify foreign agents and suppress “radical organizations.” McCarthy and his followers believed subversive elements posed a danger to the national security of the country and so justified such extreme measures, even if they included the denial of civil liberties. In this photo, men examine publications in Federal Courthouse in New York on March 12, 1957 where a subcommittee of the House of Un-American Activities Committee held a hearing. From left: Irving Fishman, Deputy Collector of Customs in New York, a witness before the committee; Richard Arens, director and counsel for the committee; and Gordon Scherer, a member of the U.S. House of Representative from Ohio. The subcommittee opened four days of hearings into the dissemination and sources of Communist propaganda. (AP Photo/John Rooney, used with permission from the Associated Press)

McCarthyism today means denying due process and civil liberties

Today, McCarthyism is synonymous with any perceived government activity that suppresses unfavorable political or social views by limiting or undermining vital civil rights and liberties under the pretext of maintaining national security. As understood, it is a means of government harassment that includes blacklisting with intent to pressure people to follow popular political beliefs. Thus anyone who makes insufficiently supported accusations or engages in unbalanced investigations against persons in an attempt to silence or discredit them is said to be practicing McCarthyism. This practice in effect represents both a denial of due process and a fundamental breach of civil liberties, thereby violating the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

The U.S. Supreme Court has referenced McCarthyism in several of its First Amendment decisions. For example, the Court explained in the library filtering decision, United States v. American Library Association (2003), that the American Library Association adopted its Library Bill of Rights in response to McCarthyism.

Justice William O. Douglas was a consistent critic of McCarthyism. He specifically criticized the phenomenon in his concurring opinion in the college student free-expression decision Healy v. James (1972) and in his concurring opinion in the political broadcasting decision Columbia Broadcasting System v. Democratic National Committee (1973).

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. Marc G. Pufong is a specialist in Public Law and Professor of Politics, Public Law and Courts at Valdosta State University. Dr. Pufong’s teaching interest and research focuses on constitutional law and judicial politics, international law and politics and human rights and conflicts. He is also co-author of three books including Georgia State Politics: The Constitutional Foundations, 7th edition (2016) with Lee M. Allen and Researching Constitutional Law, 4th edition (2013) with Albert P. Melone.