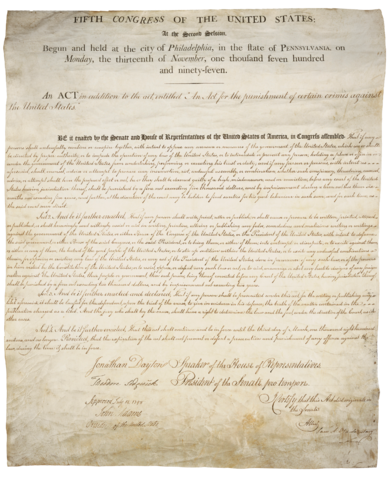

Passed by a Federalist-controlled Congress on July 14, the Sedition Act of 1798 was part of a series of measures, commonly known as the Alien and Sedition Acts, ostensibly designed to deal with the threats involved in the “quasi-war” with France.

Critics viewed the act as a thinly disguised partisan effort to control political debate until the next presidential election. The clash over the Sedition Act yielded the first sustained debate over the meaning of the First Amendment.

Sedition Act targeted editors of Democratic-Republican newspapers

The three so-called Alien Acts made it difficult to become a naturalized citizen (such individuals tended to side with Democratic-Republicans over Federalists) and gave the president power to deport without trial aliens he considered threatening. The sweeping language of the Sedition Act made it illegal, among other actions, to “write, print, utter or publish…any false, scandalous and malicious writing…with intent to defame the…government” or “to stir up sedition within the United States.” The acts were set to expire on March 3, 1801, which would mean that they could not be used by the incoming administration, if, as it proved to be, it was composed of Democratic-Republicans.

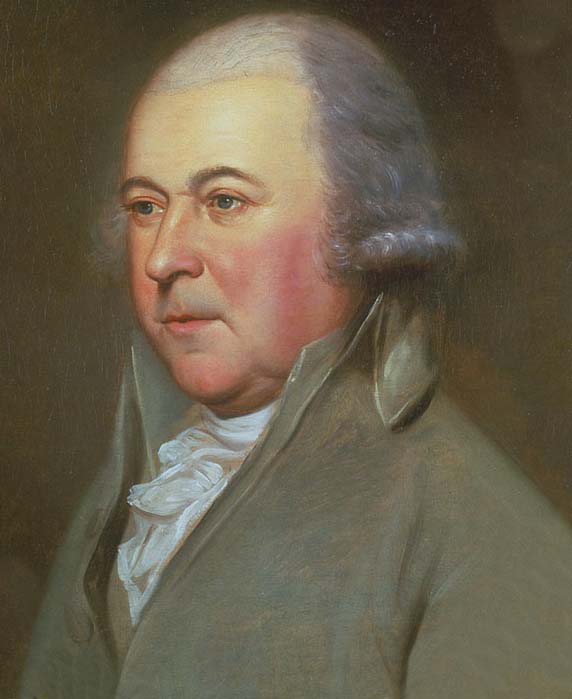

Although a case never reached the U.S. Supreme Court while the law was in effect, lower Federalist judges, including Justice Samuel Chase who was riding circuit and was later impeached in part for his partisanship on the matter, enforced the law with vigor. Scholars have traditionally cited 17 indictments and 10 convictions, many upon charges so flimsy as to be comical. Targets of the act tended to be the editors of Democratic-Republican newspapers who criticized the Federalist administration of President John Adams.

The most frequently cited prosecutions have involved Benjamin Franklin Backe, who edited Philadelphia’s Aurora, and John Daly Burk and James Smith with New York’s Time Piece who were arrested under what Federalists alleged to be federal common law.

Congressman Matthew Lyon, who owned a Vermont newspaper, and Thomas Adams and William Durrell, who respectively edited Boston’s Independent Chronicle and New York’s Mount Pleasant Register, were prosecuted under the Sedition Act. So were Benjamin Fairbanks and David Brown of Massachusetts, who had supported the construction of a liberty pole. Luther Baldwin and Brown Clark of Newark, New Jersey, were indicted for criticizing President Adams in a tavern. Other prosecutions included those of William Duane of the Philadelphia Aurora, Ann Greenleaf of New York’s Argus, Charles Holt of the New London Bee and Anthony Haswell from the Vermont Gazette.

State legislator Jedidiah Peck was indicted for circulating petitions criticizing the Sedition Act as were Thomas Cooper, who edited the Northumberland Gazette, and James T. Callender, who had published The Prospect Before Us (Bird 2016, 261).

Wendell Bird has further documented another 11 prosecutions of 16 individuals under Section Two of the Sedition Act, which punished criticism of the government or its officials (Bird 2016, 335-337). Many of these involved prosecutions of individuals who had participated in Fries Rebellion in Pennsylvania, opposing federal property taxes for national defense against the French.

Federalist judges enforced the Alien and Sedition laws with vigor. Targets of the Act tended to be the editors of Democratic-Republican newspapers who criticized the Federalist administration of President John Adams, shown here. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, painted by Charles Wilson Peale between 1791 and 1794, public domain)

Federalists thought seditious libel law was part of common law

Federalists genuinely worried that the French threat, both military and ideological, might be enough to topple the infant republic. To them, a seditious libel law was part of the English common law, constitutional under the necessary and proper clause, and an obvious instrument of defense. They believed the First Amendment embodied only the common law protection of forbidding prior restraint, or licensing. Leading Federalists thought that it was impossible to attack members of the government without attacking the very foundation of government itself.

The Federalists argued that the Sedition Act in reality expanded civil liberties. The act allowed “the truth of the matter contained in publication” as evidence in defense and gave the jury “a right to determine the law and the fact.” This contrasted with English common law, which did not admit truth as a defense and limited the role of the jury to establishing the fact of publication.

Republicans argued that regulating speech was improper

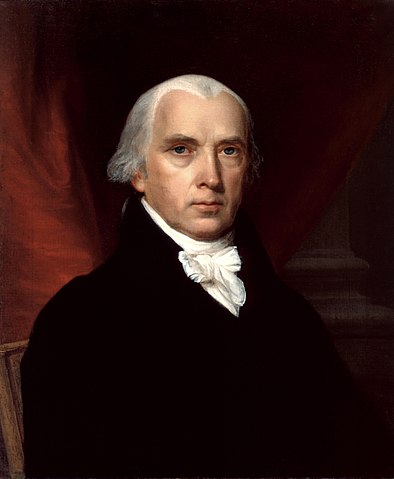

To Federalists, a seditious libel law was part of the English common law. James Madison (shown here), a Democratic-Republican, argued that the common law had evolved to meet the needs of hereditary systems, not those of an elective system. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, painted by John Vanderlyn in 1816, public domain)

Republicans countered that the Constitution expressly delegates no power to regulate speech or the press and that such powers are in no sense necessary and proper. The First Amendment, they argued, specifically prohibits the making of any law whatsoever regarding speech or the press.

In some instances, the Republicans’ arguments were directed more fully in support of the case for states’ rights, as in the case of Thomas Jefferson’s Kentucky Resolutions. James Madison, in his Virginia Resolutions and more fully in the report he authored for the Virginia Assembly in 1800, stressed the necessity of completely free and vigorous political debate for republican governments. The common law, he argued, had evolved to meet the needs of hereditary systems, not those of an elective system that necessarily requires the continuous critical examination of public officials and policies. Madison’s argument called into question not just the constitutionality of a national seditious libel law but the need for such a law at any level of government in an elective system.

Backlash to Sedition Act swept Federalists from power

The prosecutions and subsequent convictions under the Sedition Act galvanized opposition to the Federalist administration. (Samuel Chase, a Supreme Court justice, was particularly partisan toward the Sedition Act when presiding over prosecutions, and was later impeached for this.) The prosecuted Republican printers and editors became folk heroes. In the election of 1800, the Federalists were swept from power—never to return—and Jefferson, the new Democratic-Republican president, subsequently pardoned those who had been convicted under the law.

Almost 170 years later, the Supreme Court wrote in the celebrated libel case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964): “Although the Sedition Act was never tested in this Court, the attack upon its validity has carried the day in the court of history.” Today, the Sedition Act of 1798 is generally remembered as a violation of fundamental First Amendment principles.

This article was originally published in 2009. It was updated in March 2024 by John R. Vile, professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University. Peter McNamara is a Professor in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University.