Public radio grew out of the noncommercial radio stations established by universities and labor and religious groups in the 1920s. In light of the pervasive control the British government exercised over public radio, concerns about First Amendment rights of freedom of speech and press led to the establishment of the U.S. system, in which nonprofit corporations maintain primary control over the content of their shows. These nonprofits are eligible for some government funding, and even that indirect link to government has led to occasional political disputes.

FCC investigated early nonprofit radio station for Communist ties

About twenty years before Congress passed the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, which made National Public Radio (NPR) possible, a pacifist named Lewis Hill put the first of his nonprofit so-called Pacifica stations, on the air: KPFA-FM in Berkeley, California, which began to broadcast in 1949. Hill’s next stations were in the Los Angeles and New York markets.

Hill’s concept of an outlet for alternative performing arts and political perspectives met with resistance in the early 1960s, when Pacifica applied to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for a station in Washington, D.C. The FCC requested enormous amounts of documentation and questioned Pacifica’s nonprofit status because its listener-supported stations “sold” program guides. The federal agency also raised questions about content—including anti-religious and anti-government rhetoric. The frequent appearances of guests such as socialist Norman Thomas and Carey McWilliams, editor of The Nation, on Pacifica stations prompted the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Internal Security to investigate alleged communist infiltration of Pacifica in 1963.

NPR faced criticism for being both liberal and conservative

NPR was created in 1970 and began to broadcast in April 1971. Pacifica stations are not part of NPR, though both have been involved in First Amendment controversies.

During the Reagan administration in the 1980s, NPR faced criticism as being a tool of the political left. Reports issued by the Heritage Foundation and the conservative watchdog group Accuracy in Media led KUSC-FM in Los Angeles to stop carrying NPR news on the grounds of liberal bias. This criticism continued in the 1990s through COMINT, a media criticism journal, whose writers lobbied conservative members of the board of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), a source of government funding. In 1992 Sen. Robert J. Dole, R-Kans., attached an amendment to the CPB’s authorization bill mandating “strict adherence to objectivity and balance” on public radio and television.

The left, in turn, took NPR to task in 1993, when Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), a liberal media watchdog organization, released a report critiquing NPR’s morning and afternoon drive programs, Morning Edition and All Things Considered. The FAIR analysis of these broadcasts, covering September–December 1991, found little of the in-depth reporting and diversity of voices that was supposed to separate public radio from its commercial counterpart. Simmons College sociology professor Charlotte Ryan, the report’s author, argued that conservative criticism and fears of federal budget cuts had had a chilling effect on NPR.

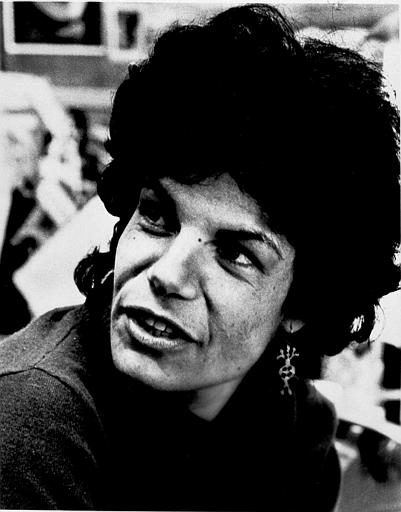

Similar to commercial radio, NPR has faced investigations and lawsuits. For example, in 1989 NPR’s All Things Considered aired news broadcasts containing federal government surveillance audio of organized crime leader John Gotti, who used a four-letter expletive or a variation of it ten times in seven sentences. A listener filed an indecency complaint against an NPR member station that broadcast Gotti’s remarks. The FCC threw out the complaint in 1991. Susan Stamberg, pictured here, co-hosted All Things Considered at the time (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

NPR has faced investigations and lawsuits

Similar to commercial radio, NPR has faced investigations and lawsuits. For example, in 1989 NPR’s All Things Considered aired news broadcasts containing federal government surveillance audio of organized crime leader John Gotti, who used a four-letter expletive or a variation of it ten times in seven sentences. A listener filed an indecency complaint against an NPR member station that broadcast Gotti’s remarks. The FCC threw out the complaint in 1991, stating that “the use of such words in a legitimate news report [was not] gratuitous, pandering, titillating or otherwise ‘patently offensive’ as that term is used in our indecency definition.” By contrast, the Supreme Court in Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation (1978) upheld the FCC’s regulation of the public broadcast of George Carlin’s monologue on “Seven Dirty Words.”

NPR was sued in March 1996 by Mumia Abu-Jamal—a death row inmate convicted of murdering a Philadelphia police officer—on First Amendment grounds, seeking compensatory and punitive damages. NPR had recorded at least nine commentaries by Abu-Jamal, which were slated to begin airing in May 1994, but they never aired. Abu-Jamal alleged that pressure from the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police and Senator Dole forced NPR to cancel his commentaries. In a federal lawsuit, Abu-Jamal claimed that Dole had threatened NPR’s funding if Abu-Jamal’s views were aired. The litigation was based, in part, on the assertion that NPR is an agency of the U.S. government. U.S. district judge Royce Lamberth dismissed the lawsuit in August 1997, saying that Abu-Jamal had failed to back up his assertion because none of NPR’s directors is appointed by the federal government.

This article was originally published in 2009. Gina Logue is a 20 year radio journalism veteran who has covered events ranging from presidential elections to the 1996 Summer Olympics. Since 2001, she has worked in the Office of News and Media Relations at MTSU and has won over 20 awards for her work there.