In Munro v. Socialist Workers Party, 479 U.S. 189 (1986), the Supreme Court considered whether ballot access restrictions placed on minor party candidates violated free association rights protected by the First Amendment.

Washington required minor party candidates to get 1 percent of the primary votes to secure a position in the general election ballot

In 1977 the state of Washington amended Revised Code 29.18.110 to provide that a minor party candidate receive at least 1 percent of all of the votes cast in the state primary in order for that candidate to secure a position on the general election ballot. To determine whether a candidate obtained the required threshold, Washington conducted a “blanket primary” where all registered voters, regardless of party affiliation, may cast a vote for a candidate from any party.

Peoples sued to get his name on the ballot

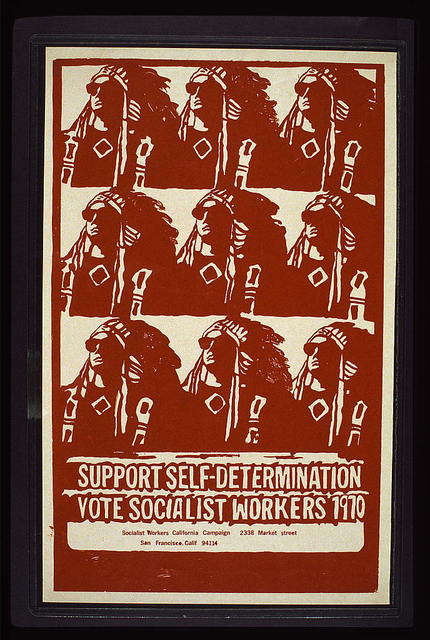

Dean Peoples, a candidate from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), appeared on the October 11, 1983, special election ballot along with 32 others. Peoples received far less (approximately 0.09 percent of the total vote share) than the required statutory threshold. Pursuant to statute, the state refused to place his name on the general election ballot.

Peoples sued Munro, the secretary of state of Washington, and the Court reversed a lower court determination holding the statute did not violate the First Amendment. The Court reviewed prior cases, arguing states have an interest in “. . . preserving the integrity of the electoral process and in regulating the number of candidates on the ballot.”

Court said some level of threshold support could be imposed

Writing for the majority, Justice Byron R. White, although saying he felt there was no “litmus-paper test,” argued that some level of threshold support for a minor party or independent candidate could be imposed by elections officials and that states should not be required to make an actual showing of voter confusion or ballot overcrowding. With that said, the Court argued that Washington’s statutory scheme was constitutionally appropriate. To hold otherwise “would invariably lead to endless court battles over the sufficiency of the evidence marshaled by a State to prove the predicate.”

Court argued that primaries leave the general election for ‘major struggles’

The Court further argued the primary mechanism is designed to “winnow out” candidates, leaving the “general election ballot for major struggles.” The Court distinguished this case from American Party of Texas v. White (1974). American Party foreclosed access to any statewide ballot, whereas Munro passes constitutional muster because it affords a candidate statewide ballot access and an “opportunity for the candidate to wage a ballot connected campaign.”

Justice White rejected the notion that “voters are denied freedom of association because they must channel their expressive activity into a campaign at the primary as opposed to the general election.”

Dissenters thought law could not survive strict scrutiny

Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote a dissenting opinion, joined by William J. Brennan Jr., arguing that the law at issue could not survive the strict scrutiny standard to which he thought it should be subjected.

This article was originally published in 2009. Daniel M. Katz is a Professor of Law at the Chicago-Kent College of Law.