This Supreme Court decision upheld a New York law allowing the loan of secular textbooks to all schoolchildren, including those in parochial schools. Justice Byron R. White wrote the 6-3 decision in Board of Education v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236 (1968), rejecting establishment and free exercise challenges based on the First Amendment.

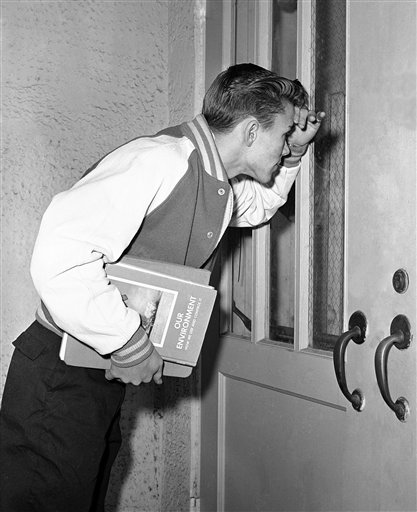

Court upheld law allowing loan of secular textbooks to children in religious schools

White argued that the decision in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), which upheld the provision of bus transportation for all students, helped to justify the textbook expenditures at issue. He further believed that the New York law passed the two-part purpose and effect test that the Court had established in Abington School District v. Schempp (1963).

Although books are more inherently religious than buses, the state limited the books it supplied to those that were secular in nature. Indeed, Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) had asserted that religious schools served both secular and sectarian purposes, and Cochran v. Board of Education (1930) had affirmed that secular textbooks served a “public benefit.”

Having thus addressed the establishment issue, White dismissed the free exercise claim as baseless because no one had shown that the law “coerces” individual religious practice.

In a concurring opinion, John Marshall Harlan II saw the law as a neutral way of advancing nonreligious purposes.

Dissenters cited admonitions against government spending on religious institutions

In his dissent, Justice Hugo L. Black denied that the case was covered by the acceptance in McCollum v. Board of Education (1948) of reimbursement for bus transportation for parochial school students. Unlike buses, books were “the heart of any school,” and James Madison had warned about using any tax funds for religious institutions.

In a separate dissent, Justice William O. Douglas objected that the law allowed schools to choose the books they wanted children to read. He cited passages from some texts used in some parochial schools to demonstrate that there was no clear line between secular and sectarian books. And he too cited Madison’s admonitions against any government expenditures for religious institutions.

Justice Abe Fortas’s dissent also focused on the fact that the law allowed schools to choose their own textbooks.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.