The Supreme Court decision in Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539 (1974), involved a class-action suit filed by a Nebraska prisoner asserting that the prison warden had violated a number of his constitutional rights.

The inmate, Robert O. McDonnell, had argued that the disciplinary proceedings within the prison violated due process, that the legal assistance program in the prison was inadequate, and that the rules for inspecting mail from attorneys were unconstitutionally restrictive.

Justice Byron R. White wrote the decision for the six-person majority, while Justices Thurgood Marshall (joined by William J. Brennan Jr.) and William O. Douglas filed partial dissents.

Supreme Court said prisoners maintained some First Amendment rights in prison

In addressing the first issue, White indicated that precedents had established that prisoners maintained some rights even in confinement, including “substantial religious freedom under the First and Fourteenth Amendments,” rights to access to courts, and rights to equal protection of the laws.

He denied, however, that these rights were identical to those that courts had imposed at hearings to decide whether inmates should be incarcerated in the first place. Specifically, White found the existing regulations to be defective in not providing individuals with advance written notices of violations against them and further written notice of the evidence. He decided, by contrast, that the Court would not uniformly impose requirements for confrontation and cross-examination of witnesses, which could be quite disruptive within a prison context. Similarly, no attorney would be required unless a defendant’s illiteracy of the complexity of the case so necessitated.

Prisoners can receive confidential mail from attorneys, Court said

Turning to the issue of mail, White observed, “While First Amendment rights of correspondents with prisoners may protect against the censoring of inmate mail, when not necessary to protect legitimate governmental interests, . . . this Court has not yet recognized First Amendment rights of prisoners in this context.”

He further observed that “freedom from censorship is not equivalent to freedom from inspection or perusal.”

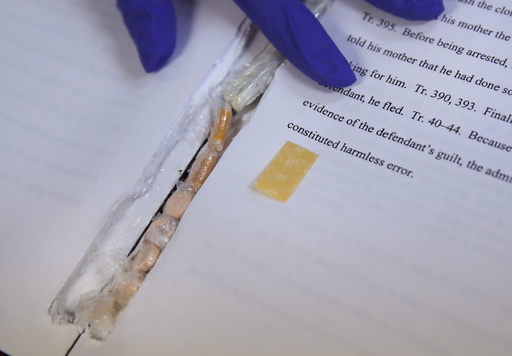

In the case at hand, he thought it was appropriate that any correspondence from attorneys that prisoners wanted protected would have to be “specially marked, as originating from an attorney, with his name and address being given, if they are to receive special treatment.”

Prison authorities would still have the right to open such mail in the presence of prisoners to ensure that such letters contained no contraband, but this would not include the right to read such correspondence. White relied on Johnson v. Avery (1969) and Younger v. Gilmore (1971) to find that the prison had to allow inmates to confer with fellow inmates with respect to their self-defense as well as their right to a “reasonably adequate law library for preparation of legal actions.”

Marshall and Douglas agreed with White’s First Amendment findings but would have required the imposition of stricter due process requirements.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.