In Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307 U.S. 496 (1939), the Supreme Court ruled that banning a group of citizens from holding political meetings in a public place violated the group’s freedom to assemble under the First Amendment. The case helped set the precedent for what is now known as the public forum doctrine, a tool used by courts to determine the constitutionality of speech restrictions implemented on government property, when it secured the right of access to public places for citizens engaging in free speech and free assembly.

City prohibited citizens from meeting without a permit

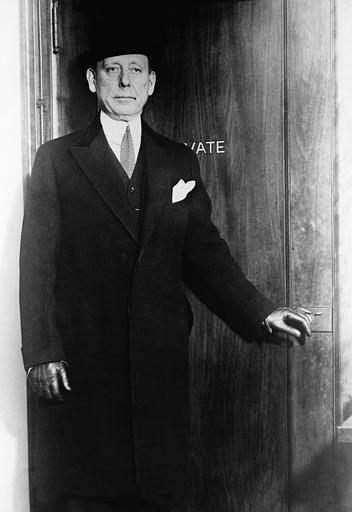

The issue in Hague was whether a Jersey City ordinance prohibiting a group of citizens from meeting in a public place to discuss and distribute literature relating to the National Labor Relations Act without a permit violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments. Mayor Frank Hague referred to the group as “communist” and a danger to the city. The Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), with support from the American Civil Liberties Union, sought an injunction against Hague claiming a denial of First Amendment rights. The lower federal courts ruled in favor of the CIO, and Hague appealed to the Supreme Court.

Court said ban violated First, Fourteenth Amendments

The Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision, but the justices disagreed on the reasoning. Justice Owen Roberts, writing for the Court, invoked the privileges and immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to argue against state abridgement of the rights of assembly and petition. He reasoned that streets, parks, and public places belong to citizens and must be protected as public forums.

While expression in public ideas may be regulated in a nondiscriminatory manner, expression cannot be prohibited. “The privilege of a citizen of the United States to use the streets and parks for communication of views on national questions may be regulated in the interest of all; it is not absolute, but relative, and must be exercised in subordination to the general comfort and convenience, and in consonance with peace and good order; but it must not, in the guise of regulation, be abridged or denied.”

Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, concurring, found that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provided this protection and thus aliens as well as citizens could claim the rights of assembly and petition. Consistent with subsequent Court decisions in Cox v. New Hampshire (1941) and Edwards v. South Carolina (1963), Stone argued that the due process clause effectively incorporated the rights of assembly and petition, as well as freedoms of speech and press, of the First Amendment.

Case was source for public forum doctrine

This decision marked the first time that the Court used the First Amendment to protect labor organizations. It also curtailed arbitrary regulations by local officials and overturned the precedent that held that government ownership of land such as streets and parks gave public officials the same authority over public space as private landlords have over their private property. As a result, public officials could not issue complete denials of access to public spaces. Thus, this case was a significant source for the public forum doctrine.

This article was originally published in 2009. Lynne Chandler Garcia is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the U.S. Air Force Academy. Her areas of research include Constitutional interpretations, the concepts of personhood, civil discourse, empathy in political behavior, foreign policy, military operations, and the art of pedagogy for underprivileged learners.