The Supreme Court decided Samuels v. Mackell, 401 U.S. 66 (1971), on the same day as Younger v. Harris and two other related decisions.

The Court unanimously upheld a three-judge district court decision denying injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment to individuals who had been indicted under New York’s criminal anarchy law — the same law at issue in Gitlow v. New York (1925) — but, in contrast to the lower court, it did so without ruling on the constitutionality of the law.

Prosecutions under anarchy laws present possible First Amendment concerns, as the individuals targeted hold dissident political viewpoints.

Court denied injunctive relief to individuals indicted under New York’s anarchy law

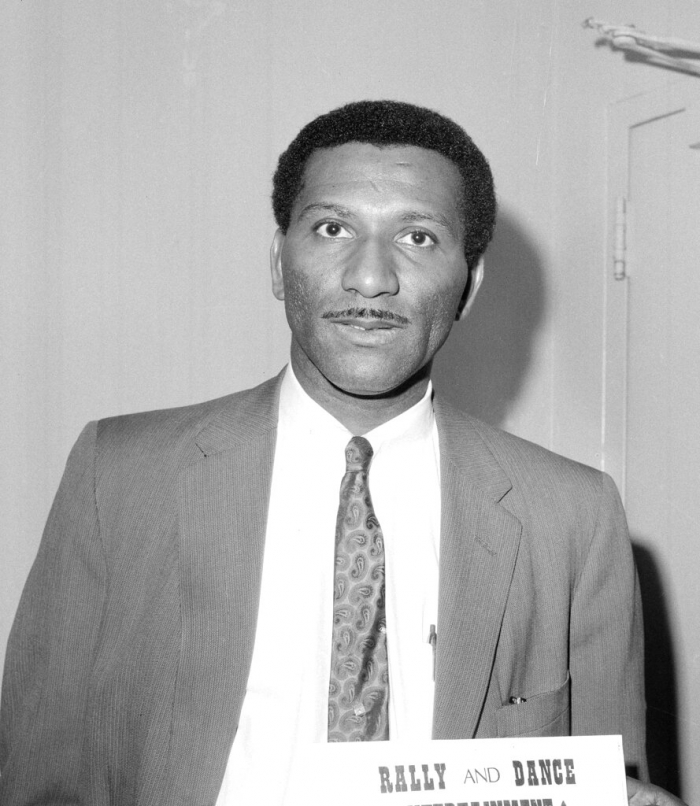

Justice Hugo L. Black wrote the Court’s decision in Samuels, which relied primarily on Younger. He saw no reason to believe that the plaintiffs would suffer irreparable injury from state prosecution.

He observed that Younger stood “for the settled doctrine of equity that a federal court should not enjoin a state criminal prosecution begun prior to the institution of the federal suit except in very unusual situations, where necessary to prevent immediate irreparable injury.” He decided that this principle applied to declaratory judgments as well as to injunctive relief.

Justice Douglas said First Amendment did not protect violence

Justice William O. Douglas wrote a concurring opinion, noting how Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) had undermined criminal anarchy laws but observing that the plaintiffs in this case were also tied to such overt acts as acquiring weapons and gunpowder and storing gasoline to start fires. He observed that “violence has no sanctuary in the First Amendment, and the use of weapons, gunpowder, and gasoline may not constitutionally masquerade under the guise of ‘advocacy.’ ”

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote a separate concurrence, joined by Justices Byron R. White and Thurgood Marshall, observing that there was no allegation in this case of “bad-faith harassment.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.