In American Academy of Religion v. Chertoff, 463 F. Supp. 2d 400 (S.D.N.Y. 2006), a U.S. district court in New York ordered the government to issue a visa within 90 days to Tariq Ramadan, a scholar of Islam, or to explain its decision to continue to exclude him from entering the United States.

The order affirmed the First Amendment rights of scholars who had extended an invitation to Ramadan.

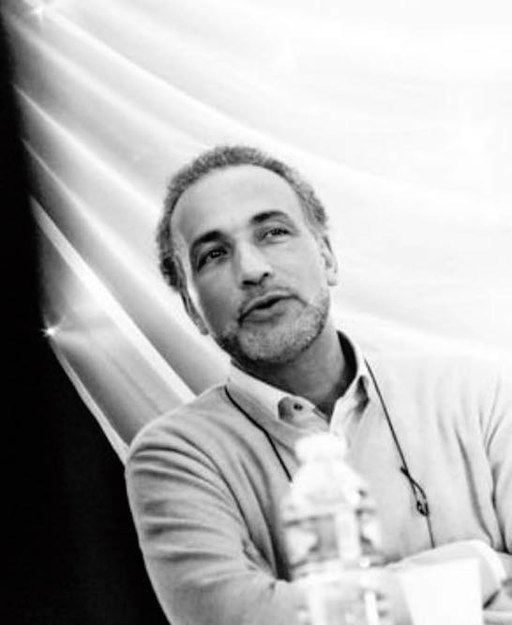

Case concerned Islamic scholar Ramadan

An internationally known Swiss-born scholar of Islam, Ramadan had published extensively and was affiliated with Oxford University. He had advocated an independent European Islam that is “fully European and fully Muslim.”

The New York court noted in its ruling that Ramadan “has consistently spoken out against terrorism and radical Islamists” and also that he had been “equally critical of Western governments” and of U.S. policy in the Middle East. Britain had “enlisted him in the fight against terrorism,” and he was “banned from entering Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Tunisia.”

Government barred Ramadan’s entry to U.S., cited Patriot Act

The University of Notre Dame had offered Ramadan a tenured teaching position that required an H-1B nonimmigrant visa, but the U.S. government revoked this visa on July 28, 2004, as he prepared to move to Indiana.

Citing the USA Patriot Act, the government initially claimed that it had done so because Ramadan fell within the category of aliens “who have used a ‘position of prominence within any country to endorse or espouse terrorist activity.’” It later withdrew this explanation, calling it “erroneous” (and thus voiding the visa revocation of July 2004).

After the United States delayed subsequent visa applications by Ramadan, he resigned from the post at Notre Dame, and the government, making no reference to its earlier approval or revocation of his H-1B visa, informed him that his H-1B had been revoked. The government also subsequently refused to act on Ramadan’s application for a B visa, filed on September 16, 2005, which would have enabled him to enter the country and participate in conferences to which he had been invited by plaintiffs.

American Academy of Religion said denial of visa violated First Amendment

The American Academy of Religion, an association of teachers and scholars, along with other groups brought suit against Michael Chertoff, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, and the secretary of state to request an injunction compelling the government to admit Ramadan to the country or alternatively to make a final decision on his visa application.

The organizations claimed that Ramadan’s exclusion, justified by the federal government under the Patriot Act’s section 411(a)(1)(A)(iii) — allowing the exclusion of prominent aliens who have used their positions to “endorse or espouse terrorist activity” — violated the First Amendment.

Court said videoconferencing could satisfy desire to hear Ramadan

In reviewing a district court’s right to issue a preliminary injunction, Judge Paul A. Crotty observed that precedents limited the issuance of such injunctions when a plaintiff could establish by a “clear showing” the likelihood of suffering “irreparable injury” and “a ‘clear’ or ‘substantial’ likelihood that they will prevail on the merits.”

Crotty cited Elrod v. Burns (1976), for the principle that “[t]he loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury,” and Kleindienst v. Mandel (1972), for the principle that “the exclusion of an alien on the basis of his speech implicates the First Amendment rights of those U.S. citizens who desire to hear the alien speak.”

Crotty observed that for purposes of a preliminary injunction, the latter interests, when balanced with others, could be satisfied through videoconferencing rather than requiring face-to-face meetings.

Court said First Amendment right to hear foreigners speak is not absolute

Crotty then examined the likelihood of success of the plaintiffs’ case on its merits.

To win, precedents established that they needed to prove

- an injury-in-fact,

- that is fairly traceable to defendant’s allegedly violating conduct, and

- that is likely to be redressed by the requested relief.

Crotty accepted that the plaintiff’s failure to interact face-to-face with Ramadan presented an injury-in-fact, namely the denial of First Amendment rights. He further found that the case was “ripe” for review.

Crotty wrote, “It is a well-established principle of constitutional law that the First Amendment includes not only a right to speak, but also a right to receive information and ideas.”

Citing Mandel, he observed that this right includes the rights of American citizens “to have an alien enter and to hear him explain and seek to defend his views.” This right, however, is not absolute. Congress had delegated power to the executive branch to exclude aliens for bona fide reasons, and courts should intervene only in cases “where the Government is unable to provide a facially legitimate and bona fide reason for excluding the alien, thereby revealing that the true reason for exclusion was the content of the alien’s speech.”

Court said government had to give reasons for visa denial

Crotty rejected the argument that the government could escape articulating reasons for its decision under the doctrine of consular nonreviewability. The government thus needed either to provide such an explanation or admit Ramadan within a reasonable time. Citing “an excess of caution,” Crotty gave the government another 90 days to issue a formal decision on Ramadan’s request.

On September 19, 2006, the government officially denied Ramadan’s visa request based on a provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act requiring the exclusion of foreign citizens who had provided material support for terrorist organizations.

Ramadan had contributed to the Association de Secours Palestinien, which had given money to Hamas.

Court later upheld visa denial after reason was given

In a subsequent review of this case, Judge Crotty upheld the denial. He stated that Ramadan, as a noncitizen, had no standing to challenge the government’s decision, which was based on clear statutory authority and subject to limited judicial review under the principle of consular nonreviewabiltiy.

Judge Crotty applied the precedent in Kleindienst v. Mandel (1972) to indicate that the government had articulated a “facially legitimate and bona fide reason for excluding Professor Ramadan.”

Crotty further noted that the denial of Ramadan’s visa was “unrelated to Professor Ramadan’s speech” and that the issue of the admissibility of an alien was a political question and therefore best left to the elected branches of government.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.