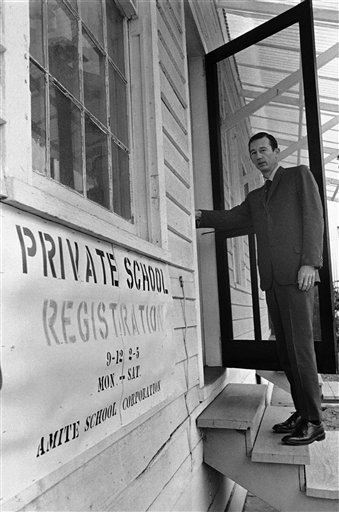

In Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973), the Supreme Court unanimously found that a Mississippi program that provided textbooks to private schools, even if the school engaged in discriminatory practices, was unconstitutional. In so ruling, it found that the requirements of nondiscrimination violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment but not the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Mississippi provided textbooks to discriminatory schools

The case was brought by parents of schoolchildren who claimed that because the state program provided textbooks to schools that excluded students on the basis of race, the state was providing direct aid to segregated education, thus violating the equal protection clause.

A three-judge federal district court upheld the program because the state had enacted the legislation in 1940 not with the purpose of creating racially segregated schools, but to provide aid to students who chose to attend private schools. The district court also found the supply of textbooks to be consistent with earlier Supreme Court opinions that allowed states to provide textbooks to students attending private sectarian schools because the books were an aid to the students, not the schools.

Court said program did not violate First Amendment

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger first affirmed the right of private schools to exist. The court had previously held that states could provide aid to private school students under the Lemon test, which required that the effect of the aid had a secular purpose, was neutral toward the advancement of religion, and did not create an excessive entanglement between the state and government. Based on these criteria, Chief Justice Burger found that the Mississippi program did not violate the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Court said program did violate the Fourteenth Amendment

However, because the Mississippi statute provided textbooks to private schools, even if they practiced racial discrimination, Burger decided that the program violated the equal protection clause. The number of private schools in Mississippi increased sharply after the court mandated that public schools be integrated, and a large majority of the students attending those schools were white. Although the Mississippi program was enacted at a time when integration was not an issue and was not intended to be used as a way of inhibiting integration, it had the effect of creating segregated education. Thus, the court found the program to be invalid. However, “the state could continue its book loan program if it required all participating schools to certify they did not engage in racial discrimination,” according to Congress and the Nation.

This article was originally published in 2009. Jonathan R. Ellzey focused on religion, political behavior, and the judiciary as a graduate student at the University of Florida. He received his law degree from Baylor University and now practices law in Burkburnett, Texas.