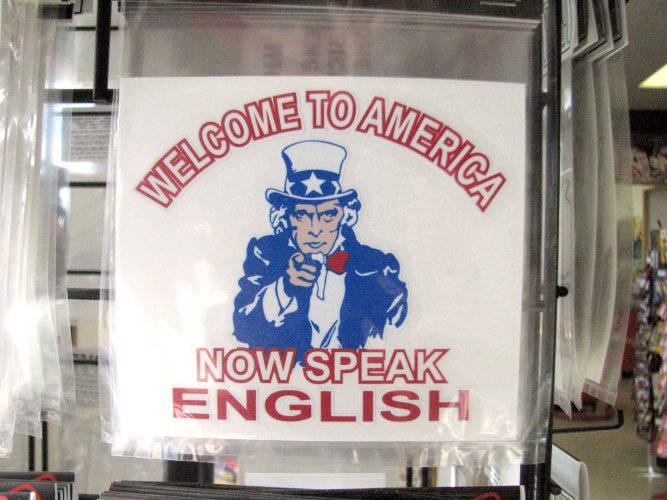

In Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923), the Supreme Court invalidated a Nebraska law banning the teaching of foreign languages to schoolchildren, finding that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. The Meyer law sprang from the nativist sentiment fostered by World War I. The Court recognized a liberty interest in parents providing an education for their children, and found that the law infringed on that interest without a proper “police power” rationale.

Teacher violated a law prohibiting the teaching of foreign languages

In this case, Robert Meyer, a teacher at Zion Parochial School, was charged with violating the state law by teaching German to a student. Nebraska had claimed that the law was a proper means to “promote civic development by inhibiting training and education of the immature in foreign tongues and ideals before they could learn English and acquire American ideals.” The Court, while acknowledging the importance of ensuring that children attain proficiency in English, concluded in a majority opinion by Justice James C. McReynolds that “the statute as applied is arbitrary and without reasonable relation to any end within the competency of the state.” He added that “mere knowledge of the German language cannot reasonably be regarded as harmful.” Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and George Sutherland dissented without writing an opinion.

The Court’s reliance on the due process clause in Meyer to invalidate state legislation was an extension of its reasoning in cases involving economic regulation such as Lochner v. New York (1905). The ruling in Meyer relied on the Lochner line of cases, but extended their logic well beyond the economic sphere. According to the Court, the liberty protected by the due process clause includes the right “to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” The Court also soon recognized that the due process clause protected against arbitrary state regulation the right to send one’s children to private schools (Pierce v. Society of Sisters [1925]) and the right to freedom of speech (Gitlow v. New York [1925]).

Meyer is good precedent for due process cases

The Court retreated from the Lochner line of cases in the late 1930s, but Meyer remained good precedent. In its famous Footnote 4 of United States v. Carolene Products (1938), the New Deal Court cited Meyer as implicitly protecting ethnic minorities. Meyer later became an important basis for the Warren and Burger Courts’ substantive due process jurisprudence in the landmark cases of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) and Roe v. Wade (1973). In Griswold, the Court suggested that Meyer protected the “spirit of the First Amendment.” More recently, Justices Anthony M. Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David H. Souter have praised Meyer as engaging in appropriately aggressive due process review of state regulations to protect unenumerated, noneconomic constitutional rights.

This article was originally published in 2009. David E. Bernstein is a university professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University, where he teaches constitutional law, among other things. He is the author of You Can’t Say That! The Growing Threat to Civil Liberties From Antidiscrimination Laws (Cato Institute 2003).