In the United States, activities that constitute the practice of law may be performed only by an individual licensed as a lawyer by the state in which he or she will practice. Under the inherent-powers doctrine, which recognizes certain authority as implicit in the judiciary, the highest court in each state sets the qualifications for the practice of law and controls the bar admission process, which is conducted by a board of bar examiners made up of lawyers and judges.

In some states, the board of bar examiners may also be connected to the state bar association. The bar admission process has produced many First Amendment-based challenges.

Bar applicants must meet educational criteria and pass certain tests

Any applicant seeking bar admission must meet certain educational and character criteria. The educational requirements in almost all states are undergraduate and law school degrees (the law school must be approved by the American Bar Association) and a passing grade on the state bar examination.

The bar examination, which is conducted over two or three days, consists of the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE), a nationally developed, standardized test, made up of 200 multiple-choice questions and covering six areas of law (constitutional law, contracts, criminal law, evidence, real property, and torts); the Multistate Professional Responsibility Examination (MPRE), which tests legal ethics and is administered separately three times each year; and locally written essay questions on a variety of legal subjects deemed important by the state’s bar examiners.

A growing number of states are also including the nationally developed Multistate Essay Exam (MEE), which consists of standardized essay questions, and the Multistate Performance Test (MPT), made up of three 90-minute skills questions covering legal and fact analysis, communication, problem solving, resolution of ethical dilemmas, and organization and management of a lawyering task.

In the United States, activities that constitute the practice of law may be performed only by an individual licensed as a lawyer by the state in which he or she will practice. Under the inherent-powers doctrine, which recognizes certain authority as implicit in the judiciary, the highest court in each state sets the qualifications for the practice of law and controls the bar admission process, which is conducted by a board of bar examiners made up of lawyers and judges. In this photo, Franklin Pierce Law Center students are sworn in as lawyers at the State Supreme Court in Concord, N.H., Friday, May 14, 2010. (AP Photo/Jim Cole, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Bar applicants must have ‘good moral character’

The second set of criteria speaks to the applicant’s character and fitness for the practice of law, usually referred to as the requirement of “good moral character.” The bar examiners seek and check background information that may reveal the applicant’s character such as academic discipline, arrests, convictions, bankruptcy, and involvement as a party in civil litigation. Most states also require the applicant to produce character certifications from the law school attended and from others who know the applicant.

Communist Party affiliation has led to First Amendment challenges by bar applicants

The bar admission process has led to numerous First Amendment-based challenges, particularly when an applicant has been denied because of past political associations or beliefs. In In re Anastaplo (1961) and Konigsberg v. State Bar (1961), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the denial of bar membership to individuals who refused to answer questions related to their membership in the Communist Party of the United States, although, earlier, in Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners of New Mexico (1957), it had used the due-process clause of the U. S. Constitution to overturn a decision denying bar admission to an individual simply because he had been a past member.

In Konigsberg, the Court noted that “good moral character” is an unusually vague concept, but the Court did not prohibit its use in the bar application process. Although bar examiners are given wide latitude in determining whether an applicant meets character standards, in Willner v. Committee on Character and Fitness (1963) the Court held that due-process guarantees apply and that an applicant denied admission on character grounds must be given the reasons for the denial and an opportunity for a hearing before a neutral body.

Decisions in Baird v. State Bar of Arizona (1971) and In re Stolar (1971) further limited earlier rulings disqualifying bar applicants who refused to answer questions about membership in communist-related organizations. And in Law Students Research Council v. Wadmond (1971) the Court ruled that states could refuse entry to those who wanted to destroy the government by force.

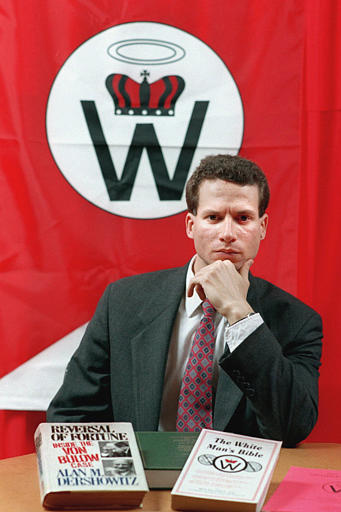

In 2002, the state of Illinois refused bar admission to Matthew F. Hale, leader of the World Church of the Creator, which advocated white supremacy, stirred considerable controversy. In 2016, the state of Maryland denied admission to a candidate Otion Gniji in part because of online postings deemed offensive by bar authorities.

Decisions in Baird v. State Bar of Arizona (1971) and In re Stolar (1971) further limited earlier rulings disqualifying bar applicants who refused to answer questions about membership in communist-related organizations. And in Law Students Research Council v. Wadmond (1971) the Court ruled that states could refuse entry to those who wanted to destroy the government by force. In 2002, the state of Illinois refused bar admission to Matthew F. Hale (pictured here in 1999), leader of the World Church of the Creator, which advocated white supremacy, stirred considerable controversy. (AP Photo/Kari Shuda, File)

Lawyers must demonstrate good character

Once admitted to the practice of law in one state, an individual with sufficient practice experience (usually five years) may be able to seek admission to the bars of other states without taking a bar examination if the states involved have a reciprocity agreement. Otherwise, the lawyer must successfully complete each additional state’s bar examination.

All lawyers, however, whether admitted with or without a bar examination, must demonstrate good character and fitness. ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct 8.2(a) prohibits lawyers from making false or reckless statements about judges. Lawyers have been disbarred for inflammatory speech about judges, other lawyers, and other public officials. For example, Maryland disbarred an attorney in 2014 for impugning the integrity of judges and other officials.

No unified or national system is in place for admission before federal courts, so each court sets its own criteria. At the trial level, the most common requirement is that one must be admitted to practice law in the state in which the federal district court is located. For admission to practice before the appellate federal circuit courts and the U.S. Supreme Court, usually admission to practice law in any state will suffice.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Peter A. Joy is the Henry Hitchcock Professor of Law at Washington University in St. Louis. He is a former General Counsel for the Ohio Chapter of American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and a former member of the Legal Committees for the Ohio Chapter and Missouri Chapter of the ACLU. He has represented clients with First Amendment issues including freedom of expression, academic freedom, and right to petition the government in state and federal courts at both the trial and appellate levels as well as authoring amicus briefs focusing on First Amendment issues.